Welcome back readers, and welcome, new readers –

With violent conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza, Israel, and elsewhere continuing to create suffering, it’s often hard to know how to respond, other than with continued prayer. The mothers and children living in these places are especially on our minds and hearts.

In thinking about this, we were reminded of the artwork of Bruderhof member Sebastian (‘Bastel’) Huessy, who himself fled war as a child and whose art was occupied with themes of suffering and redemption. In this post we’d like to share some of his work and thoughts with you. At the end of the post are reflections on his life and work from his daughter Jessica, who lives in the Darvell community with her husband and children.

Sebastian was born in 1934 in Germany on the Rhön Bruderhof, a little more than a decade after the Bruderhof was founded. Four years later when the Nazi government gave the Bruderhof twenty-four hours to leave the country, he and his family moved to the Cotswold Bruderhof in England. The temporary refuge in England ended as World War II escalated, so at the age of six he travelled with his family and other Bruderhof members to Paraguay, where he grew up. In 1961 he left the Bruderhof and moved to Hartford, Connecticut, a difficult period in his life as he tried to make sense of the world around him.

While working at various jobs, he started evening classes in psychology. “I wanted to find out what makes man tick, what can go so wrong that people lose their mind and, actually, their soul. Not that it did me any good, but it did point me to one thing: what makes man tick is love. Even psychology, at a scientific level—which is fruitless in itself—has to admit that it is love and contact with others that makes a person function.”

To express his feelings, Sebastian turned to art. His first woodcuts were simple, but deeply expressive. “Imprisoned” (1966) represents a convict in prison garb clutching the bars of his jail. Sebastian called it “a self-portrait of my inner, depressed self.” He took it to the admissions office of an art school in Hartford. It was all the portfolio he had, but he was accepted to the school on the strength of it. At art school he learned many new techniques, including etching and bronze casting.

In the meantime, the social movements of the 1960s affected him powerfully. He threw himself into the Civil Rights and anti-war movements, joining demonstrations and marches. He volunteered at a free school for high school drop-outs from the inner-city ghettos, where he taught art for a year.

Meanwhile, he discovered he could make a living with his artwork. He started a business and sold his art at shows up and down the East Coast. But in 1977 Sebastian decided to return to the Bruderhof. “The real artists,” Sebastian said, “give their whole lives to their art. Many have done that. Van Gogh, Riemenschneider, others—they were martyrs for their art. When I returned to Christian community, I decided to give my life to make the greatest art of all: a life of brotherhood. It really is a work of art, and probably, the toughest one to achieve.”

Below is a selection of Sebastian’s artwork with notes on each piece.

Sebastian was keenly aware of the environmental movement that was gaining momentum in the 1960s. His personification of the earth is a woman who seems to stand aside, watching in sorrow while her treasures are plundered.

“Poor people have to do a lot of waiting, and it is very humiliating, tiring, and painful. It often forms their habits and character: waiting in a food line, waiting for a bus. When you are poor you have to wait all the time.

“Yes, waiting—when do you wait and when do you have action? You can’t just wait for change. It has to be fought for. Yet there can be a right time for action, and a wrong time too.”

“I was portraying a shepherd, but I was thinking about what is in this shepherd—the quietness, and again the listening, being close to nature, with the lamb in his lap. I wanted total quiet to speak out of that face.

“Unless we are quiet, we can’t hear. It’s one of the most beautiful things of the spirit: that we can be alone and quiet before God and let the stars impact us.”

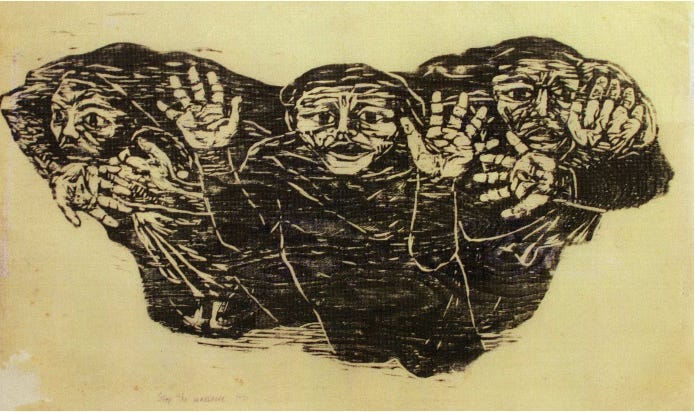

Cut into a sheet of rough plywood four feet long, this was the largest woodcut Sebastian ever made. It is clearly a work of protest in the style of Käthe Kollwitz, whose influence is notable throughout Sebastian’s work.

Here, he reacts to the media reports of gruesome atrocities in Vietnam and the ongoing violence against black people in the U.S., including in his home city of Hartford.

The figures peer out at the viewer as if they were calling through a glass window or encased in some other medium. They could be the spirits of those who have been murdered returning from the afterlife to make their urgent appeal or to warn of judgment to come.

This etching combines several of the themes that Sebastian returned to repeatedly. The cave represents the interior world of the human soul, and the three characters represent spiritual versions of the physical senses—seeing, hearing and feeling. These are the soul’s separate faculties for finding truth.

One character gazes outward, through the mouth of the cave, at the sun, a powerful image of which Sebastian said, “In the clouds is the face of God the Father, the beautiful sun, the light.” Two other characters turn inward. One listens intently with closed eyes for the interior voice of the conscience. The other feels with his hand the heat of a small flame, a tiny semblance of the sun, the spark of God within the human heart.

A skeleton, a memento mori, seems strangely animated. It reaches its hand toward the sun, suggesting perhaps that even a soul in whom the spark of God has died can be reanimated.

This etching is one of the few works Sebastian produced in which the subject listens and looks simultaneously. The figure kneels as if in worship, with his hands cupped around his ears, his eyes wide-open. All his spiritual senses combine to apprehend the over-powering message of the cosmos.

Sebastian said: “I am always mesmerized by the universe. I just can’t understand it—the distances and the magnitude of it. It has such a power of peace, and it all hangs together up there in the heavens. Have you ever floated down a two-mile wide river, like the Paraguay River, lying on your back, gazing in absolute rapture at the whole canopy of moving constellations? I recommend it.”

“When I made this piece I was listening a lot to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the ‘Ode to Joy.’ You get the message: all men will be brothers. I wanted to make these two as though they are about to break into a smile at any moment.”

Reflections from a daughter: Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” hung on our living room wall above the family sofa. Always. As Papa read us the C.S. Lewis’ Narnia series, as we sang folk songs, and in those more chaotic moments as he berated us giggling, shrieking children to behave. It was always there. Through every childhood crisis and family upheaval, van Gogh’s familiar dots and swirls twinkled on, assuring me that all would be well. Papa spent hours with us on that same sofa, poring over volumes of Michelangelo, da Vinci, Rembrandt and Kathe Kollwitz, enthusiastically explaining the artists’ biographies, the mediums they used and the significance of their work. We didn’t understand everything, but his enthusiasm was contagious.

At the living room table, Papa’s work-roughened fingers grasped a stick of charcoal. I watched the soft black circles go round and round in sweeping ovals on the paper until suddenly, as if by magic, a face would emerge. Intrigued, I lingered on to see what would happen next. These were the random spare moments that Papa filled doing what he loved best. Other times, blended pastels filled a large piece of paper in overlapping shapes of blue, purple and gold, or wood shavings dropped to the floor as a rugged shepherd, bent in adoration, took shape under a carving knife. Perhaps best of all was watching a lump of clay being transformed into a donkey, Papa’s fingers carefully shaping the pointed ears and hooves.

It never occurred to me until years later that Papa had no access to proper art materials as a child growing up in the jungles of Paraguay, where every scrap of paper was treasured, saved and re-used. Instead, a childhood of adventures exploring risky jungle territories, encountering deadly snakes, surviving tropical illnesses and insect bites, and harvesting oranges and mangos coloured his boyhood mind, forming fertile ground for the creativity that would later explode through his artwork.

Papa would be the first one to admit he wasn’t perfect. But through his own personal experiences he was given a gift: compassion. I’ll never forget seeing his eyes well up with tears and hearing his voice tremble as he recounted what he’d witnessed at a bomb-struck, sanctioned hospital in Iraq when he travelled to Baghdad with a peace organization in 1998. Or how he told us of the racial injustice that he saw ruining young lives during his time in Hartford. Hardest of all for Papa was the suffering of innocents – women and children.

All of this is deeply reflected in his artwork: compassion for human suffering, from violence to injustice, to the humiliation of the poor and downtrodden. Throughout Papa’s life, there was always a certain restlessness, always something he was concerned about or tragedies in the world that grieved him. Not to say that our house didn’t rock with crazy laughter at times, or that there wasn’t plenty of joking around. But there was always a keen awareness.

When I said good-bye to my father for the final time on a warm August day three years ago, van Gogh’s “Wheatfield with Reaper” hung over his head. The harvest was ripe, and he’d participated.

I couldn’t help thinking of one of my favourite works of his: “Go in Peace”. All was well now. For always. In that golden glow of the eternal city and the embrace of brothers was the permanent healing of all the world’s suffering. And I knew that Papa believed in that.

He said of this work, “I made “Go in Peace” thinking of the deeper meaning of the City of Peace, of God’s presence, and of two men embracing each other in farewell. It came out of knowing what life in brotherhood offers.”

Reflection from Trudi: Art is often referred to as a way of self-expression which it is, but I feel the term can be misused. I think the self we express through art should be our God-made self, our unique, divine spark of creativity. Seeing Bastel’s art for the first time, I was impressed how it cries out against injustice and evil. It shows deeply compassionate insight and I marvel at his ability to express those intense feelings. It made me reflect on my own abilities and what I do with creativity.

Why do I do art? I have never used art in the way Bastel did. He had a special gift and purpose.

For me, creativity is a release. Bad days turn into good ones when I have an outlet for creativity. Luckily teaching requires a heavy dose of creativity in many ways so I get daily opportunities.

I also feel that living in community with others provides numerous occasions for celebrations of all kinds and those times call for purpose-oriented creativity.

Other times creative expression can also just be a leisure activity although it is never purposeless. I don’t do any one thing often, but I enjoy sewing, painting, designing and cartooning or drawing posters and cards, writing a poem, playing violin, planting a garden, arranging flowers, making a video to celebrate an anniversary, cooking a meal, etc. Most recently a friend and I made and decorated a birthday cake, collaborated on creating a water-balloon toss game for kids, and arranged a ceramics session with an elderly elementary school arts teacher to try some wheel work. That was my first time at a potter’s wheel in about six years and I wondered why I’d ever stopped.

So I am grateful for the opportunity to praise God and love others through creativity. I believe each of us has gifts for that purpose.

Reflection from Norann: My beloved step-mother, Roswith, was an artist and art teacher her entire life. She introduced us, her children, and all of her students to a variety of art styles and influences from early cave-art (I remember Mom making actual cave paintings with us from paints we created from ancient recipes using ochre and egg) right through to Jackson Pollock (Mom – who loved realistic art – always described her disappointment with JP’s “White Light” after standing for hours with her university class in NYC to view it for a few minutes.)

Because Mom, like Sebastian, was a WWII refugee (both of their German parents fled with her from Germany to England to Paraguay) she especially resonated with the art of Käthe Kollwitz. Mom loved art that had meaning and significance, and I remember her introducing us simultaneously to Michelangelo’s Pieta and Kollwitz’s Mother with her Dead Son (photographed here by my cousin Walter, a Berlin-based artist). In retrospect, I realize Mom resonated with the suffering in Kollwitz’s art because of the trials in her own life, including, like Kollwitz, the loss of a child.

But even though she inspired us with great works, Mom never discouraged us in our own artistic efforts. I was definitely the least artistic of her children, but Mom always encouraged me to “draw with my words” or “try photography.” I do both now but still love to surround myself with pictures and paintings, especially from children nearby.

I have a wall in our hallway set aside as a dedicated art gallery, and all the community children know they can contribute anytime. My neighbour’s mom illustrated two children’s song books when she was in high school (the glorious Sing through the Day and Sing through the Seasons) and the artistic apple hasn’t fallen far from that particular tree in the case of her and her children.

For your enjoyment:

That’s it folks. Appreciate the season you are in.

Norann, Marianne, and Trudi

Thanks for this - the words and Sebastian's artwork - read and viewed with delight, gratitude, and a tear or two, for the understanding, wonder, compassion, and joy expressed so clearly.

Eg. "Have you ever floated down a two-mile wide river, like the Paraguay River, lying on your back, gazing in absolute rapture at the whole canopy of moving constellations? I recommend it.”

Absolutely!

Thank you.

Matt Holland (son of Gerty & Leslie)

Thanks for introducing these beautiful artworks to me. Huessy's pictures spoke to me, but I must admit for sheer whimsy I love the aerial numbat!!!