Welcome back readers, and welcome, new readers –

February 22 is the anniversary of the execution of three college students in Munich in 1943. Brother and sister Hans and Sophie Scholl and their friend Christoph Probst were members of a resistance movement known as the White Rose.

The lead editorial (quoted at length below) of the Fall 2024 issue of Plough Quarterly tells the story of the White Rose. When we read it, we decided to dedicate a post to reflecting on it. All three of us were introduced as young teens to the story of Sophie Scholl. Her letters and diaries sparkle with idealism, joy in life, and humor as much as with indignation at the tyranny she sees around her; reading them, it’s easy to imagine being her friend, discussing music and books and dreaming about the future with her. All the more, knowing that she died at 21 is shocking.

The story of the White Rose continues to resonate because of the clear moral line between immensely courageous and principled young people and the Nazi state and its functionaries. Even though our lives haven’t (yet) presented the starkness of the choices that they had to make, reflecting on their story helps clarify the choices we make in daily life.

“Freedom!” was what Hans Scholl and two fellow students painted on walls around Munich during the night of February 3, 1943. The three friends, all in their twenties, were members of the anti-Nazi movement known as the Weiße Rose or White Rose. They painted the word freehand, three feet high, using tar-based black paint that would be tough to scrub away. For their other slogans – “Down with Hitler” and “Hitler the Mass Murderer” – they used stencils. Two of them did the work while the third stood guard with a pistol.

Since the summer before, Hans Scholl and other members of the White Rose had been writing and distributing illegal leaflets that demanded, “Freedom! Freedom! Freedom!” These short manifestos condemned “National Socialist subhumanism,” decried the war and the German extermination campaign against Poland’s Jews, and called for resistance and sabotage. By this point, the group had access to a duplicating machine and was anonymously distributing thousands of copies in public places and by mail, as well as through their networks in other cities. Hans Scholl served in the army as a medic during academic breaks, and had seen firsthand the horrors of the Eastern Front. The midnight graffiti campaign was the White Rose’s response to Germany’s loss of its Sixth Army at Stalingrad, where at least 1.2 million people, including 200,000 German soldiers, had died.

On a morning two weeks later, Hans and his twenty-one-year-old sister, Sophie, set out to distribute the White Rose’s sixth and last leaflet on the University of Munich campus. “Fellow Students!” it began. “Devastated, our nation stands before the downfall of the men of Stalingrad. … The day of reckoning has come, the reckoning of our German youth with the most despicable tyranny ever endured by our nation. In the name of all German youth, we demand from Adolf Hitler’s state our personal freedom…. Our nation is on the verge of rising up against the enslavement of Europe through National Socialism, in the new, devoutly believing breakthrough of freedom and honor!”

When they had placed most of their 1,500 leaflets in stacks around campus, Sophie, on impulse, tossed a pile of copies down from the balustrade in the atrium of a university hall. A janitor saw her, locked the building, and called the police. She and Hans were arrested by the Gestapo on the spot. He remembered too late that his pocket contained the draft of a seventh leaflet by his friend Christoph Probst. The Gestapo seized Probst, also a student and a father of three, shortly afterward. Four days after the initial arrest, the three were condemned to death for treason in a two-hour trial and executed. (Other White Rose members, including Hans’s fellow graffitists Willi Graf and Alexander Schmorell, would be executed over the following months.) In court, Hans Scholl insisted that he had acted freely: “I knew what I took upon myself and I was prepared to lose my life by so doing.”

…

After their brief trial on the morning of February 22, 1943, Hans Scholl, Sophie Scholl, and Christoph Probst heard their death sentence at 12:45 p.m. The authorities in Berlin were eager for the sentence to be carried out that same day. The local Gauleiter commissioned a carpenter to build gallows for a public hanging, but was overridden by Heinrich Himmler, who worried about making the students into martyrs.

In prison, where they spent their last three hours, Christoph received baptism and communion from a Catholic priest. Hans and Sophie wanted to do the same, but held back out of respect for their devoutly Lutheran mother, and instead received communion from the Protestant prison pastor.

At four o’clock, the three were informed that a final appeal for clemency had been denied, and that the execution would be at five.

Shortly beforehand, the prison guards waived their own rules and allowed the three to share a last cigarette. The Scholl siblings had been able to say farewell to their parents. Christoph, whose wife was unaware of her husband’s fate (she was in hospital with childbed fever), now knew that he would never see his four-week-old daughter. All the same, he seems to have been at peace. When it was time to say goodbye, the guards would later recall him saying to the others, “In a few minutes we’ll see each other again in eternity.”

Sophie was taken to the guillotine first; Christoph was to be last. Two minutes after she had gone, the guards came for Hans. The official record of execution notes that the time elapsed between removal from the cell and death was fifty-two seconds and that “the condemned was tranquil and composed.” It adds: “His last words were, ‘Long live freedom!’”

The previous October, Sophie, in a letter to a friend, sketched out her own sense of what freedom is for. We are, she suggested, to use the freedom the Creator has given us to choose the beauty of his plan for ourselves and for the world. Despite the horrors of human history, she was confident this plan would prevail:

“Isn’t it mysterious – and frightening, too, when one doesn’t know the reason – that everything should be so beautiful in spite of the terrible things that are happening? My sheer delight in all things beautiful has been invaded by a great unknown, an inkling of the Creator whom his creatures glorify with their beauty. – That’s why man alone can be ugly, because he has the free will to disassociate himself from this song of praise. Nowadays one is often tempted to believe that he’ll drown the song with gunfire and curses and blasphemy. But it dawned on me last spring that he can’t, and I’ll try to take the winning side.”

You can read the rest of the editorial here.

Trudi – in Spring Valley, southwest Pennsylvania

This story always strikes me deeply, with a gut-twisting challenge: could I do that? Would I do that? Risk everything and ultimately lose my life so that Truth can prevail? Countless men and women have done the same throughout history and while I admire them, I do not want to follow in their footsteps. Martyrdom is not appealing. At the same time, I want to do what is right, and I trust that I will readily give my life for goodness and Truth.

Sophie Scholl, a young woman like myself, spoke words that often run through my mind, forcing me to reflect on what I am wanting in life. Is it just safety and happiness? She writes,

The real damage is done by those millions who want to “survive.” The honest men who just want to be left in peace. Those who don’t want their little lives disturbed by anything bigger than themselves. Those with no sides and no causes. Those who won’t take measure of their own strength, for fear of antagonizing their own weakness. Those who don’t like to make waves—or enemies. Those for whom freedom, honour, truth, and principles are only literature. Those who live small, mate small, die small.

It’s the reductionist approach to life: if you keep it small, you’ll keep it under control. If you don’t make any noise, the bogeyman won’t find you.

But it’s all an illusion, because they die too, those people who roll up their spirits into tiny little balls so as to be safe. Safe?! From what? Life is always on the edge of death; narrow streets lead to the same place as wide avenues, and a little candle burns itself out just like a flaming torch does. I choose my own way to burn.

I used to wonder where Sophie got such courage. Like any of us, she was sometimes afraid: “I know that life is a doorway to eternity, and yet my heart so often gets lost in petty anxieties. It forgets the great way home that lies before it.” Belief in eternal life and dogged faith gave her the strength she needed: “I will cling to the rope God has thrown me in Jesus Christ, even when my numb hands can no longer feel it.”

So how do Sophie’s words change me? I could go out, pick a cause, live, and die for it. But I think a cause will find me if it hasn’t already. I just have to remain open, willing, and ready for God to lead me into the battles He needs me to help fight. I want to keep my flame fearlessly burning, always anticipating the joy of eternity.

Norann - in Danthonia, New South Wales, Australia

Marianne and I were in middle school when a friend of Sophie Scholl, Traudl Wallbrecher, spoke to our class at Woodcrest School in the mid-1980s.

I think that every one of us students can still remember where we sat that day. I can even remember what I wore – a maroon dress with yellow roses around the neck. I remember feeling that it was vaguely significant that I was wearing roses, but wishing they were white.

We were an energetic class, but hardly a chair creaked as Traudl told us of her growing friendship with Sophie Scholl, the formation of the White Rose as a protest to the emergence of Nazism, and her conviction that she must do something to stop the evil.

Traudl, who was studying psychology at Munich University, described how, on the afternoon when Sophie Scholl tossed leaflets through the university atrium and was arrested after being betrayed by a janitor, Traudl was hurrying back from gym class. She noticed police locking down the building, remembered she had White Rose leaflets in her school bag, and quickly ducked into a bathroom. In a locked toilet stall, she shoved the leaflets to the very bottom of her bag and piled her sweaty clothes on top, hoping the police would be deterred and look no further.

Traudl came out of the bathroom stall, brushed her hair, looked in the mirror and said a farewell to herself, then moved back into the hallway with her head held high. She walked bravely toward the doors where each student was being searched, and allowed her bag to be rummaged through by the guards. They looked no further than the gym clothes and Traudl walked free.

Traudl, who was obligated to work as a nurse for government, participated in the dissolution of the Dachau concentration camp, where she witnessed first-hand the devastation she had protested against. She dedicated the rest of her life to working for peace, community, unity, and ecumenism, founding a Catholic lay community that has had an enduring friendship with our Bruderhof Community.

For Marianne and our classmates and me, Traudl’s story, and the connected story of Sophie Scholl and the White Rose Movement, remain an inspiration for faith and true courage.

Sophie loved the writings of the mystic Augustine of Hippo, and I often wonder which were her favorites.

Perhaps it was this one:

Hope has two beautiful daughters; their names are Anger and Courage. Anger at the way things are, and Courage to see that they do not remain as they are.

Marianne – in Woodcrest, upstate New York

My mom gave me a book about the White Rose when I was about twelve, and like everyone who encounters this story, I imagined myself in the place of the students, hoping that I would have made the right choices in the same circumstances. Now, though, it’s the students’ mothers that I think of, as they were probably about the age I am now. It’s clear from Sophie’s writings that she came from a close, loving family – she was the second of six siblings. I imagine the parents’ pride in their children’s moral courage turning to fear and horror with news of their arrest, trial, and execution. There’s an unforgettable moment towards the end of the 2005 movie Sophie Scholl – The Final Days where her mother comes to say goodbye to her hours before her death. “Sophie, denk an Jesus,” (Sophie, think of Jesus) is her farewell message to her daughter.

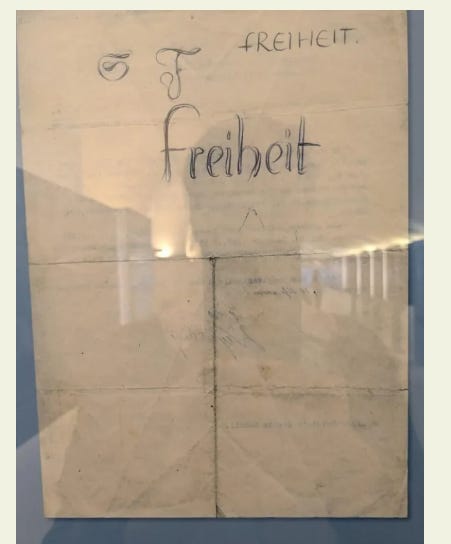

Last September I spent a day in Munich and visited Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. There are several memorials in the atrium where the students were arrested, and a small museum in the basement which is where I saw this document which was in the files of the Chief Prosecutor. It’s the reverse side of a piece of paper with the word “Freedom” in Sophie’s handwriting: a schoolgirl doodle that was used as evidence in a capital trial.

Here’s some recommended further reading:

Freiheit! The White Rose Graphic Novel by Andrea Grosso Ciponte is an excellent introduction to the White Rose story. The leaflets they printed distributed are reproduced at the back of the book.

At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl – what it says on the cover. An important book especially for teens and college students.

On almost her last day on earth, Sophie listened to Schubert’s Trout Quintet and wrote about it to a friend. Read what she wrote and listen to this joyful music in her memory.

Things we’re doing / enjoying

Marianne

After a very cold start to the year, it’s finally maple sapping weather: in order for the sap to run, daytime temperatures need to go above freezing while it’s still freezing at night. Yesterday we tapped our trees and set up our sapping shed and boiler. We collaborate on this every year with another Woodcrest family whose children are similar ages; it’s fun to have a recurring common project like this where once a year we spend quite a bit of time together. It’s extremely satisfying to go from tree to tree on a winter evening collecting sap and then standing around the sapping fire as the long evaporating process begins.

Trudi

We all need ‘favorite things’ to keep us going in life. In the last two weeks, I did one of my favorite things: preparing Korean dishes with Koreans. I was in New York where all the Korean Bruderhof members living in the USA were gathered for prayer and discussion about how and where God is leading our young Bruderhof community in Korea. We are excited that we have a place where Koreans and non-Koreans who are seeking to follow Jesus can all live and meet together. Myself and several other singles and families who have lived at or visited Yeongwol community feel like we left our hearts there, so a gathering of Koreans is home for us. And of course, we celebrated with some Korean cuisine.

I enjoyed participating in two days of food preparation: LA galbi, kimbap, japchae, fried mandu, sesame cabbage salad, fruit platters. The cooks were some of my Korean “aunts” as I call them and they did a wonderful job. (Sidenote: anyone can cook Korean for their family, but shopping for and cooking Korean food for almost 300 people is no small feat!) The food was delicious and I enjoyed sitting with Marianne’s family and watching their valiant attempt to eat with chopsticks. . . .

Back in Spring Valley this week, I helped with another Korean meal: more vegetable chopping, more Korean practice, more laughter, more joy.

Norann

We’re in the last weeks of summer here in Australia (Autumn begins on March 1st) and the Orchard Swallowtail Butterflies are putting in a steady appearance.

They used to be rare on our property, but with the increase of trees, shrubs, and other vegetation they are now regular late summer visitors. The male butterflies are quite territorial and will even try to chase away birds.

Often, the butterflies will alight on nearby branches and vines for a longer time of rest, which means I attempt to capture their wing detail on camera.

That’s all for now folks. Enjoy the season you’re in!

Thank you, belatedly, for writing about the White Rose. In these troubled times I do wonder if I have the courage those young people had. I hope so - but I admit I hope not to be tested!

Norann - What a superbly beautiful photo of the butterly. Thank you.