Welcome back readers, and welcome, new readers –

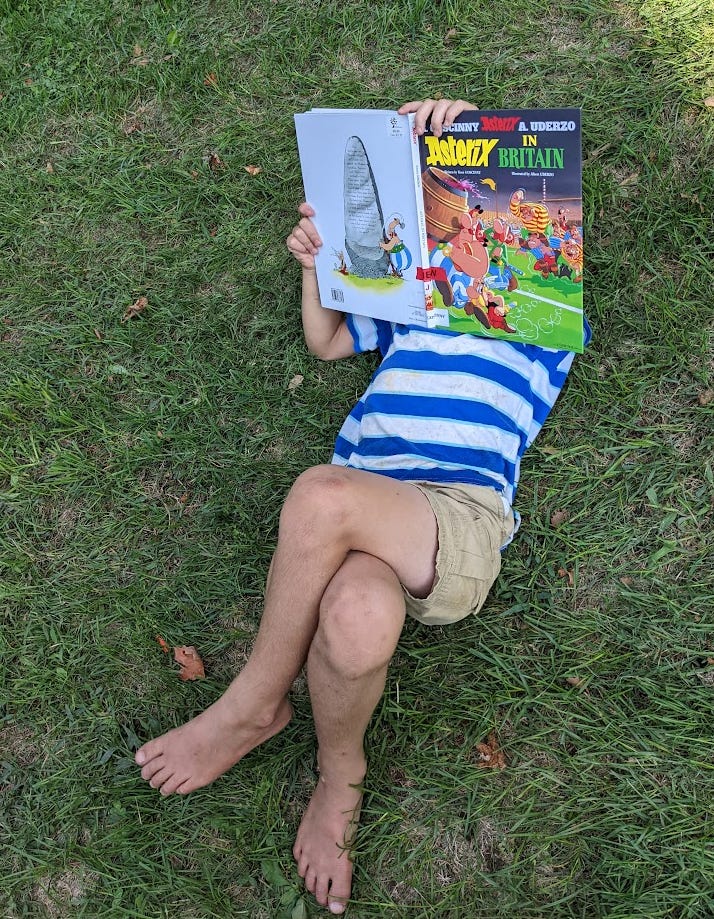

Studies seem to show that people (including children) who read for leisure in actual paper books both enjoy and understand what they are reading more than people who read on screens. But in order to read paper books, they need to be found in the places where we live – see the essay “The Library at Home” by Zito Madu about what it’s like to grow up surrounded by books.

So in this post we’ve invited Trudi’s mom, Veronica, to write about the role of books in making a home. Veronica is the mother of nine daughters who are now all grown up; she lives with her husband Tobias at the Holzland Bruderhof near Jena, Germany.

Trudi – in Spring Valley, southwest Pennsylvania

Introduce my mother? I’ve been wondering how to go about doing that. For starters, my mom has my love and respect, and I have her partiality to dark chocolate. While I’ve developed my own interests and hobbies, I seem to have also inherited her love for music, art, good reads, gardening, and generally keeping my hands busy. (Dad would add “overly” to the latter.)

Perhaps a mom of nine doesn’t know how to relax. She and my dad really did raise me and my eight sisters. Their work is not over, it’s just changed. In some ways, it’s easier. For one thing, no more teenagers (the last turned twenty this month). But in some ways it’s harder, and more complicated. Oh for the days when a bandaid stopped the pain, and a kiss and a story at bedtime were enough.

But, then again, perhaps it still is enough. Perhaps precious memories can only bloom when the last storybook closes. And even after the narrative details of the last family read-aloud fades from mind, the love between reader and listeners remains.

Six months ago I was in my parents’ house in Germany. I’d just got back from two years in Korea and I was about as disoriented and lost as I’ve ever felt in my life. It wasn’t just jetlag.

My parents’ small apartment did not feel like home to me, but the very first evening saw me kneeling at their small bookshelf (very much smaller than it used to be) and touching books of my childhood, pulling them out and flipping through them one by one.

Suddenly, those books made me feel at home and memories of other books came rushing back. Like when mom encouraged me to read Saroyan’s The Human Comedy or when my dad introduced me to James Herriot’s stories of life as a vet in the Yorkshire Dales. I read both.

This post is about keeping good books in the home. But it’s really about love—the love of parents who nurture their children with literature.

Now from my mom:

In our home there was no television. Nor did we miss it. But books, yes, we had books. No, to be honest we didn’t have many books at first, especially not many considering we were eight children. In my early years we moved so much, plus, come to think of it, I guess we were what people would consider poor, so we only had a few books. But we weren’t poor, not really. We were rich!

We had parents who loved us and who delighted in telling stories. My earliest memories include my father telling stories about a little bear and his friend who came alive at night and had all kinds of adventures. That little bear translated in my mind to “Prickly Teddy”, the coarse-haired toy bear from whose tummy Brahms’ Lullaby used to tinkle forth upon the turn of a key, but who thereafter spent most of his life (or at least his daytime hours, I imagined) sitting on top of Daddy and Mama’s wardrobe waiting for Daddy to repair his music box. The stories Daddy told spun on in my mind, and I could just see the bears creeping about in the shadowy bedroom.

The story we begged for most from my mother was “tell us about when you were little . . . about when you slid down the roof until your dress had a hole in the back.” “Did you get a spanking?” The sloping roof of the shed, the high snowbanks that allowed Mama and her friends to scramble up, the glee with which they whizzed down, and the crestfallen looks when they were scolded for the damage to their clothing, were clearly etched in my mind.

As for actual books, one of the first I remember was a board book: Mother Goose rhymes in the shape of a shoe, the old woman who had so many children she didn’t know what to do. I studied the numerous children, tumbling about the house, and pondered about whether she really spanked them all soundly before she put them to bed. And yes, even now, as I go up steps, holding one of my grandchildren by the hand, I count them, reciting “one, two, buckle my shoe, three, four open the door. . .” all from that book.

Our paternal grandparents lived in Switzerland and, on the rare occasion when a package arrived from them, it often contained one book, obviously chosen with care. That is when I first met “Joggeli” who was too lazy to shake down the pears, and “Ursli” who wanted to carry the biggest bell in the parade, his sister “Flurina” and her wild moorhen, plus the seven brothers who were turned into ravens until their little sister rescued them from the glass mountain. These books were read until they fell apart (they have been rebound, and now as my grandchildren enjoy them, are falling apart again). We absorbed these stories completely, although the books were all in German which only my parents spoke at that time.

I can’t even remember when I learned to read for myself, but I do remember that all through my childhood Mama continued to read aloud to us, and Daddy too. Often at the end of mealtimes or after the little ones were tucked in, we’d get to hear another chapter of the “family book.” There was a sacred rule that one did not sneak look-ahead-peeks. Generally, I was honest , but I remember creeping quietly across the living room floor hoping the boards wouldn’t squeak and surreptitiously opening Meindert Dejong’s The House of Sixty Fathers at the book mark...I just had to know what happened next.

That was the year we moved to South Main Street, Torrington, Connecticut, and I found summer intensely boring. As the “responsible” older sister who was supposed to help in the vegetable garden and find something to do around the yard, I soon tired of swinging the little ones on the swing set, or twizzling on the tire swing Dad had put up. We lived next to a Drive-Thru car wash and aside from scouring it for refundable coke bottles and reading bits of very questionable literature discarded in the waste bins, I sat on the steps and waited for the “Weekly Reader” as the mailman made his rounds.

But once a week, baby packed into the buggy, everyone trotting dutifully behind, Mama took us to the library. I still see the big, dusky, carpet-lined aisles, the tall windows and stern-looking adjoining rooms, a place where one automatically whispered. And there was a kind of candy-land board game where you moved along a marker for each book you read, and you got a penny at the end (you could buy one Bazooka Joe bubble gum for a penny then). That was when I became an insatiable reader.

I still attribute the value placed on books in our home to be the chief catalyst for learning to read. And what is a home anyways? It is a place of refuge, a retreat. A place you want to be. It’s the shelter, sanctuary, and stronghold of the family. The family that nurtures and instructs its offspring, or is supposed to. In other words, it is in the family where children develop character, learn discipline, cultivate tastes for everything from food to fashion. It is important, then, what is offered or not offered there, right? And through the books my parents read aloud to us we grew to love different cultures, lands, and lifestyles. My mother, who went to a tiny country school, had not had the chance to explore a wide range of books in her childhood. She told me she had read every single book on the couple-of-shelves-library in their classroom, however. And though her school days ended at fifteen or sixteen, her education certainly did not. Throughout her thirty-seven years of widowhood, right into the last three months of her life when she was suffering from cancer, she brought home books of all descriptions from the library: children’s books, biographies, books on foreign lands. At first, I could read aloud to her for half an hour each afternoon, then only ten minutes before she could no longer concentrate, but always that reaching out to worlds beyond her walls remained a part of her.

Time passes on, and so do family habits or traditions. Ask my children. They will have their own recollections of reading around the supper table. The longer the story, the shorter the candle in the table center burned. One child dripped wax patterns on their napkin, while her sister was busy pinching the orange peels into the candle to produce a satisfying flare of flame. The stories we read meanwhile were often neither deep nor complicated, but edifiying nonetheless. The depictions of France through Natalie Savage Carlson’s delightful Orphelines might seem antiquated in today’s world, yet the French food markets that today’s French tractor drivers threaten to block are the same food markets Armand visited in The Family under the Bridge. It might seem trivial, yet the books you read your children will pique their interest to learn more. And I am sure Ralph Moody’s Man of the Family will help nail a few boards onto their character houses.

A man’s character is like his house. If he tears boards off his house and burns them to keep himself warm and comfortable, his house soon becomes a ruin. If he tells lies to be able to do the things he shouldn’t do but wants to, his character will soon become a ruin.

Norann – in Danthonia, New South Wales, Australia

Literature, especially reading aloud, was an integral part of our household routine when our sons were younger. One of the results is that we now get to enjoy the integration of memorable lines into daily parlance (which used to only be speech but now includes texts).

Some examples from our family follow – please add your family classics in the comments.

When someone is working through something in a messy fashion: “He came up the rockery by degrees, shedding buttons right and left.”

(Tom Kitten, Beatrix Potter)When someone needs to make a point: “I am the Lorax, I speak for the trees.”

(The Lorax, Dr. Seuss)When someone is feeling mixed emotions toward another person: “Sam did like Alice and he didn’t like Alice and he felt he was going to cry.”

(Days on the Farm, Kim Lewis)When a household object is being looked for and can’t be found, the answer is always: “We are sitting on our own hats.”

(The Great Pie Robbery, Richard Scarry)When someone is upset: “I am affronted.”

(Mrs. Tabitha Twitchet in Tom Kitten, Beatrix Potter)When someone wants the food to be shared at the table: “Pass the damn ham.”

(To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee)When something is very large, it is “as if it had been built round her by someone who knew they were wearing arm-chairs tight about the hips that season.”

(Carry On, Jeeves, P.G. Wodehouse)When directions are needed: “By the shore of Gitche Gumee, By the shining Big-Sea-Water….”

(Hiawatha, Longfellow, and yes, we read the entire poem, out loud, from an 1868 edition of all of Longfellows works, and, yup, the boys wanted us to keep reading so we followed up with The Courtship of Miles Standish. If you want small children to get sleepy, read Longfellow out loud, and also, watch for rhyme schemes in their spoken language the following day.)When multiple food items are being listed: “…and thirteen jars of minced moose meat!”

(Pierre Bear, Richard Scarry)When plans change: “Not coming on Christmas day?”

(A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens)Arriving at a new place: “This palace hath a pleasant seat.”

(Macbeth, Shakespeare)When leadership is required: “Lead on, Macduff!”

(also Macbeth)At bedtime: “To sleep, perchance to dream….”

(Hamlet, Shakespeare)When finishing describing a place, any place at all: “And a river runs through it.”

(A River Runs Through It, Norman Maclean)

Marianne – in Woodcrest, upstate New York

Our family’s list of book sayings would have some overlap with Norann’s: you could come into our house and quite often hear someone say “I am affronted!” Another favorite from that “master of English prose”1 Beatrix Potter is for when something spills and, like in Mr Jeremy Fisher’s house, it’s “all slippy-sloppy in the larder.” As Veronica writes, families develop cultures in all kinds of ways: maybe the glue that holds yours together is a favorite show or movie, or sports statistics, or Bob Dylan lyrics (“if there’s an original thought out there, I could use it right now”). But books are a special part of a family home: they hold thoughts and stories and facts that can help us explain and understand ourselves. If my son leaves Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy face down on the table, I can pick it up and remember a little better what it felt like to be a teen. The dark-haired girl curled up on her bed with The Secret Garden and a diminishing pile of M&Ms used to be me, and is now my fifth grade daughter, equally outraged at being called forth for chores. When I read Carl Sandburg’s Rutabega Stories to the five-year-old for the many dozenths time, I can hear the echo of my Grandpa reading it to me and remember his love and wisdom (“if you can’t find what you’re looking for, look for what you can find”) and see Grandma’s inscription written to my dad on his birthday many years ago, wishing him “a year with as many kites, gliders, and campfires as the law allows.”

The important thing is for the books to be in your house. If you’re reading on an electronic device, how will your children know that what’s making you crack up is not a YouTube short but Murder Must Advertise (“It is a far, far, butter thing that I do”). The third-grader who, like Eustace Clarence, prefers facts to stories,2 needs to be able to go the bookshelf and find the book about rocks and minerals when he has a special stone to identify. A guest who arrives early for family dinner will not be left wondering what to do when there’s a pile of Findus and Alfie books on the couch along with an eager audience. The child who resisted The Hobbit last year is bored on a rainy Saturday and before he knows it has arrived at the Last Homely House. Eventually the teenager will (I hope) pick up The Imitation of Christ and Mere Christianity; if he is used to seeing Pilgrim’s Progress around the house, maybe he will remember to open it when the going gets tough for him.

There is one more aspect to all this, which is that pretty much any time someone picks up a book, it will turn out to be one that someone else was in the middle of, and, to once more quote Beatrix Potter, “Then there was no end to the rage and disappointment of Tom Thumb and Hunca Munca.”

That’s all folks. Enjoy the season you are in!

CS Lewis, writing about Beatrix Potter in a letter to a friend in 1942:

It was the Professor of Anglo-Saxon [Tolkien] who first pointed out to me that her art of putting about ten words on one page so as to have a perfect rhythm and to answer the questions a child would ask, is almost as severe as that of lyric poetry. She has a secure place among the masters of English prose.

“He liked books if they were books of information and had pictures of grain elevators or of fat foreign children doing exercises in model schools.” Although our son does not like pictures of fat foreign children as far as I know.

Who said "If you have a book you will always have a friend"?

A perfectly fine tour of cultures, traditions, families. All because of reading. My mother was certain that lives are enriched by reading, so my brother and I were provided a good variety of reading materials. Funds were tight from dad’s blue collar factory job, but through extensive home gardening, baking, making jellies and jams, and making our britches and shirts with her sewing skills, dad’s pay was sufficient and we ate a healthy diet. And wore out the binding of many a book.

Thank you all so much for sharing about the importance of reading and books in your lives. And for prompting the recall of same in my family.